|

|

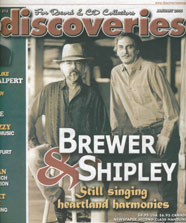

||||||

|

||||||

|

played it live. We were working on

Tarkio at the time, and Neil Bogart, who was the head of our label, Kama

Sutra, came backstage and told us we had to record it. "The song came out about around the same time as Hunter Thompson's Fear And Loathing in Las Vegas, and we always thought that if they ever make a movie out of the book, 'One Toke' would have to be the theme song. Well, they did [make the movie], and it was [the theme song.] It's still our biggest hit, and we get nice royalty checks from it four times a year. It's ironic , 'cause one of the checks comes in just before April 15th. I sign it right over to the government, so my taxes are paid by the song they tried to ban." "We weren't telling people to get high," Shipley said in a separate interview from his home in Rolla, Mo., three hours up the road from Brewer's house. "It was a song about moderation, maybe desperately crying for moderation in our own lives. At that time we'd been on the road too long. It was a metaphor for too many Holiday Inns, too many sleepless nights, too many easy girls, and too many bad habits. Today we're many thousands of tokes over the line." While the duo recognizes "One Toke" as the highlight of their career, the story doesn't end or start there. The big hit came after years of struggle on the folk circuit and continues to this day. Reunited after a seven-year hiatus, they still play festivals, concerts and private parties for fans. "There was no big break up," Brewer said. "We'd been on the road too many years, it almost killed us." "We were burned out," Shipley agreed. "In the words of a song popular at the time, I fooled around and fell in love with a lady I met on the road. I knew it wouldn't last if I didn't stop touring. So I did, and it did, and we're still married." Shipley dropped out of music to pursue his interest in film, video and folklore. He started Tarkio Communications, created the Oral History of The Ozarks Project, a non-profit organization that produces documentaries about life in the Missouri Ozarks and works at the University of Missouri at Rolla making documentaries about University life. "I just got back from a 10-day shoot at the Gerace Research Center in San Salvador in the Bahamas, a foundation located at an old submarine tracking station," Shipley said. "The island is where they think Columbus made his first landfall. It's got huge biodiversity and geological diversity, people come down to study fish, wildlife and plant life. You don't have to be a scuba diver; you can snorkel, see incredible marine life, creatures that here here from 100,000 years ago to the present. I had 25 or 30 students and got sunburned and infected as well as all kinds of great video. "The Oral History of the Ozarks Project was set up to do stories about the Ozarks. There's a generation of Depression-era mountain folks here, and their stories weren't being told. I follow people around and let them tell their stories and illustrate it with video. It's not just old guys talking about the way it used to be. They show you. One guy used to make railroad ties, and he actually hacked out a railroad tie for us. They paid 'em 10 cents a tie. He said, I forgot how hard that was. It's been 55 years since I did the last did it." Shipley also makes films about traditional music. "I did one called Precious Memories about Doug and Rodney Dillard's father who was a fiddler and harmonica player. John Hartford was one of their pals and grew up with them. I followed their dad around to tell the story about how traditional music gets passed down in the family unit. Pop Dillard danced and played the fiddle at the same time, which Hartford later did. He got it from Pop Dillard." Meanwhile, Brewer kept making records. Dan Fogelberg produced his first solo album, Beauty Lies, with guest vocals by Linda Ronstadt and J.D. Souther. He toured to support the disc but nothing on the scale of B&S's endless road trip. "I started promoting myself as a songwriter. I've had cuts by Stephen Stills, The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, and Don McLean. Quite a few bluegrass bands have cut a song on Beauty Lies called "Hearts Overflowing." I just found out a Czechoslovakian band is going to cut it, if you can believe that." In 1986, seven years after the duo split, radio station KCFX in Kansas City asked them to do a one-off concert. A sold out crowd gave them an enthusiastic welcome, and the boys started writing performing again. "I don't know if we're on Fantasy island with our fans," Brewer said. "But people say we sound just as good as we ever did. I don't know if it's true; we have to transpose some tunes because a bit of that high end is gone." "When they offered us the reunion concert, we couldn't believe how much they were going to pay us," Shipley said. "After that, people made us offers, and we weren't burned out and we weren't supporting a band so we do short little tours, and still have a family life. While we were out there, we were writing again and eventually had enough songs for an album. We made enough money selling T-shirts at the concerts to pay for the album and started One Toke Productions to put it out." "Having recorded for five majors, we know how the system works," Brewer said. "With the advent of the internet you can have control. You can market your music, keep whatever you make and work at your own pace. Our new motto is "35 years and still smokin',' which we still do, in both senses of the word, but the pace is slower. We don't play clubs; we don't want to play for drunks anymore and don't have a desire to be on the road all the time. I'd like to get together more often and work up some of the older things the fans are always asking for, but when you've written hundreds of songs they tend to get replaced by the new songs." Their first reunion album, 1993's Shanghai, was produced with Lou

Whitney and featured the guitar of D. Clinton Thompson, both of the

legendary Morells. "We didn't have a big budget," Shipley explained.

"We had musicians from Ozark Mountain Daredevils, David Allen Coe's band and

some guys who used to play with us, so we cut it fairly inexpensively.

We did the basic tracks in two days. Then Mike and I went in and redid

the guitar and vocals." |

||||||

|

Shanghai has more of a rock feel than a lot of B&S albums, with a lot of

tough guitar work. "it was a natural progression from Tarkio Road.

It's the album that should have followed Tarkio, only we were a

couple of decades off." The songs on Shanghai are as good as the familiar B&S tunes. "Take More Money" rides a funky New Orleans-meets the Caribbean-meets the Ozarks rhythm to tell the story of a poor boy and his free-spending girlfriend. "Dance With A Lady" is a bouncy uptown rocker dedicated to Shipley's wife. "Streets of America" is a classic B&S protest song, full of dark images, but ultimately it's a homage to the spirit of America. "When we were on the road," Shipley said, "we met a lot of émigrés. We saw how tough it is to get here. Half the people who tried to come here died on the way. The ones who made it are the real Americans, and that's still true today. People who walk across the desert to work and send money home, they're the real heroes." Although Brewer & Shipley live close enough to visit, both are busy with their families, and Shipley has a steady University job. When they do get together to play and write, it's just like the old days. "We get ideas when we're picking," Shipley said. "If I get an idea and think there's something there but it isn't writing itself, I don't try to push it. I bring in Mike. We write good stuff on our own, but what we do together is usually better. I like metaphor, and Mike's more literal. When my metaphors become unrecognizable to the general public, he can bring it back to something people can understand." In 1997 B&S cut Heartland, a return to an earlier, folky sound. "We wanted to keep it simple and acoustic," Brewer said, "but it actually was one of the most technological CD's we'd ever done, so it was a challenge. Tom had a brand-new home studio, and for some reason, we couldn't record an acoustic guitar or vocal on the equipment, so we had to record it backwards. We programmed and played all electric and computer stuff first then had transferred to digital tape so we could record the acoustic guitars and vocals and do the overdubs, but I'm proud to say it turned out pretty good. On Heartland the trademark B&S sound, two voices singing together in ever-shifting harmonies, is intact. It's a technique they perfected so long ago that it's now second nature. "We've always arranged the vocal lines so you can't tell what's the harmony and what's the melody, but I can't say any conscious thought went into doing it." Brewer said, "Even today, we show up, go on stage, and strangely enough the old computers kick in and we do the shows, no rehearsals, no warm-ups." Heartland, as you might expect from it's title, is an extended love song to the past, present and future of the Missouri countryside that has been home to both men since the late 60's. "Cimmaron River" uses a modified pow-wow drumbeat to praise the working people who have poured their blood, sweat and tears into the soil, from the original Native inhabitants to today's vanishing blue-collar tribe. "Watching The Stars Go By" is a beautifully melancholy song of longing and loss, while "Is Anybody Home" is a gentle ballad that questions the direction our country is currently taking. There's always been an element of social commentary in our music but more personal and spiritual than political," Brewer said. "Today I'm not only concerned about the direction the country is going in, I'm concerned with the direction the planet is going in. I have kids and grandkids, and right now it doesn't look too good." Brewer addresses some of those concerns on Retro Man, his second solo album and the most political statement either partner has ever made, down to the warning label on the back of the package: "This CD contains material defending the Bill of Rights and the Constitution of the United States and may lead to independent thinking." "Back in the Tarkio days, I didn't think it would ever get this bad," Brewer said. "I still had some hope, but today I don't know. As I say in 'Rolling With The Punches', I might be wrong, but someday I could be arrested just for writing this song. It's pretty bad. Tom calls George Bush the Al-Zarqawi of the Christian al-Qaeda." Retro Man is a collection full of love and hate, joy and frustration, hope and despair. "Freedom Avenue" is an epic history of America's protest movement and the villains in power that continue to plague us. "It's a never-ending song, because you can always add another new verse about whatever stupid things politicians are doing," Brewer said. "Hearts Of The Children" is a prayer to the spirits of the Native people who lived in harmony with nature before the coming of the white man. "Rolling With The Punches" describes the post-Sept. 11 world we live in with a mixture of ironic humor and harsh reality. "I don't call the album political, because I don't believe in politics. I vote locally, where there is some chance of changing things. What we need is a multiparty system like in Canada, cause there are so many segments of the population that aren't represented. A friend said, 'What we need is a two party system.' I think he's right. They're the same thing here, one big crock of shit." BEFORE THE FIRST TOKE Brewer grew up in a musical family in Oklahoma City. Both parents played the piano; his brother Tim is a songwriter; he contributed "Blood In The Water" to Retro Man. His other brother Keith is a multi-instrumental wiz, and his sister Charley is a singer/songwriter and guitarist. "I sang on the radio when I was 4 years old. I played drums in a rock band in high school. I sold my drums and bought a Martin. I hung out at a folk club called Buddhi and opened for bigger acts. As soon as I graduated, I hit the road, booking myself. I had a stable of clubs I could revisit, coast to coast, and was earning a living. Tom was doing the same thing, and we met at a folk club in Ohio named the Blind Owl. "In '65 the club scene collapsed. I'd started writing with a guy name Tom Mastin; we moved to L.A. and got a record deal with Columbia, but before we finished recording Mastin split. My brother Keith came out and redid Mastin's vocals. We released one single as Brewer & Brewer, "Need You" a pretty ballad by Mastin & Brewer, a real collector's item. We also wrote a tune called "Bound To Fall" about a bad LSD trip Mastin had. [B&S] did it on ST11261. Steve Stills and Manassas recorded it too." Tom Shipley was born in Bedford, Ohio, just outside of Cleveland. "I went to Baldwin-Wallace College in Berea, Ohio, majoring in geology," Shipley recalls. "I wanted to be a naturalist and had minors in Comparative Religion and Cultural Anthropology. I was in rock bands in high school. I picked up guitar in senior year after hearing Pete Seeger. The folk scene was starting, and I got swept away. I started with the Alan Lomax book of folk songs, and the next thing I knew, I was registering black people to vote and protesting the war. "In college I was singing in coffee houses, opening for Josh White, Ian & Sylvia, and Bob Gibson. Before I went to grad school, I was doing the folk circuit making one or two hundred bucks a week. I had a VW bug that cost a penny a mile to drive. I never got my master's, when the folk thing started to peter out, I headed to San Francisco for the Summer of Love. When I realized the music industry was in L.A. not San Francisco, I headed south." Brewer & Shipley crossed paths on the folk circuit and reconnected in L.A. Brewer: "Tom looked me up and rented a house near mine. We started hanging out and writing, and it clicked. Since we had the same folk background, it wasn't hard to come up with stuff. A&M signed us as songwriters. They wanted us to go into an office and crank out songs, like a regular office job, but that wasn't our cup of tea. In fact, it made us hate tea. I had a large closet in my apartment with a window and a sawed off tree stump table. We wrote all the songs for our first album there." Shipley: "We saw ourselves as singer/songwriters and performers in the model of Vince Martin and Fred Neil. We wrote a lot of the songs but never had much luck pitching them. We were very stylized and never figured out how you go about pitching tunes." Brewer & Shipley cut Down In L.A. for A&M. The album title may have been a slam at the way the music business was run. Brewer: "We didn't like the album or L.A. There's a Dylan line 'you ask why I don't live here, honey how come you don't move.' That's how we felt about it. So we moved to Kansas City," Shipley. "A&M was paying us 125 bucks a week as staff songwriters. After we moved to KC they stopped paying us, so we no longer belonged to them." In Kansas City B&S made their home at a folk club called the Vanguard. They started Good Karma Productions and played all over the heartland - colleges, high schools, clubs and county fairs. They created enough buzz to get signed by Buddah/Kama Sutra. Brewer: "FM radio was new then, and we were all about albums, not singles. Neil Bogart (head of Kama Sutra) wanted to get into the FM thing. This was before he became the King of Disco with Casablanca and Donna Summer." THE ALBUMS ~ Weeds ~ Shipley: "Our manager knew Nick Gravenites, he cut the demos that got us the Kama Sutra deal, so we headed out to San Fran to cut the album. The band was heavy blues guys - Mark Naftalin on piano, Mike Bloomfield on guitar, Nicky Hopkins. It was probably hard for them to do our stuff, but when you play out of your genre it forces you to get creative. They'd played together for years, so we moved them toward the center, after we found out where the center was. The sound was a synthesis of the band, the producer and us." Brewer: "We'd been playing those songs live, and we butted heads [with the band and Gravenites], but we were open to input. We didn't give the producer free reign 'cause we knew what we were about, but when another musician plays something that made us go wow, we were open to it." |

||||||

|

Weeds was one of the first folk-rock albums to use pedal-steel

guitar, then considered strictly a country instrument. Brewer: "We were folk artists, and country fell into that category. The Byrds had just done Sweetheart Of The Rodeo, and people were starting to get a country feel in their music. Along with Sweetheart, Weeds and Tarkio were the first folk pop albums to incorporate the country thing. If it weren't for country music and the blues, rock 'n' roll wouldn't exist. When you consider all the blues guys that were playing on those albums, it had to be some kind of hybrid." Despite the soon-to-come controversy over "One Toke", the title Weeds passed without commentary. B&S settled on the title because the land they'd just bought in Missouri was overgrown with weeds. The counterculture pun was unintended. ~ Tarkio ~ Shipley: "Tarkio was more political than Weeds. We had a cult following and got a lot of play on underground radio. On the road we'd meet all the hippies running away from home or the war, so we wrote about what we saw, a generation that was on the move. We'd get threatened at truck stops by the truckers, so we expressed the feelings of our generation. We just had a mic and a recording studio, and, hopefully, some talent. Around the time that Spiro cited 'One Toke,' we did an interview on Armed Forces Radio with a lady interviewer and she played "One Toke" and 'Oh Mommy' I'm sure the engineer wasn't listening to the lyrics ("It says right there in the constitution, it's really OK to have a revolution"), so those songs got played all over Vietnam. You'd be surprised how many fans we have that are Vietnam vets and thankful for those songs. I think that's why [Agnew] came after us." ~ Rural Space ~ Rural Space features more covers than any other B&S album. Their time on the road was starting to take it's toll. Shipley: "Mike and I had hit the wall, we were starting to become commodities and didn't have time to get inspired or write. There was a lot of complaining going on. I don't hold that up as a shining example of a B&S album." Brewer: "We were on the road so much we didn't have time to write. Some of those songs were written in the studio, which is not the best way to do it. They didn't have the chance to develop. We like to write 'em and road test 'em before we cut 'em cause when they're on vinyl or whatever they're on now, they stay that way forever. ~ ST11261 ~ The title of ST11261 was a slam at the record label, but it's a solid collection, on par with Weeds and Tarkio. Brewer: "Music is just another commodity to [the majors], and since the album is product, we named it that. We found out later that [the title] didn't make anybody in the Capitol Tower, from the ground floor up, very happy, John Boylan produced. The guys that went on to become The Eagles sang backup on one of the tracks." Shipley: "The title was a much resignation as protest. I was spending too much time trying to have too much fun at the bar. I was laughing to keep from crying as the old song says." ~ Welcome To Riddle Bridge ~ Welcome to Riddle Bridge brought the first part of the B&S saga to a close with an album that sounded little like the folk rockers of a mere six years before. Strings and a horn section were added to spice things up. Shipley does not have fond memories of the sessions. "I had an album cover planned for that - Kentucky Fried Brewer & Shipley. The players were great, but they were playing all those canned parts. We had a song called "Brighter Days" that mentioned the sea. [Steel player] Reggie Young did one of his dying seagull sustains that he does so well. Listen to "Indian Summer" arrangement on Riddle Bridge and compare it to the Weeds sessions, and you'll hear the difference. That will tell you all you need to know about Nashville music. The San Francisco musicians, Gravenites and Mike and me, originated the Brewer & Shipley sound. It was a cooperative venture. In Nashville they only have one way of doing things, and it wasn't our way." These days Brewer & Shipley are content keeping a low profile and cherry-picking the gigs they do. They're also happy with the reissues that keep the music available for fans old and new. "Our fans kept us alive," Shipley said. "We like to pay them back; if we can get the old stuff out on CD, we do it. I don't care about the money, I do it for the love... and some money. We also have a lot of older fans; when they turn 50 they often hire us to play at their birthday parties. We like those gigs better than any concert." |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

||||||